The difference between real and lifelike

A few ill-borne thoughts on writing character

I’m writing this newsletter while under a blanket, recovering from a bad bout of the stomach flu, or the wrath of a food borne pathogen. As I am so often when ill, I’m feeling philosophical, and solipsistic, and indulgent in the abstract.

Recently, a friend of mine, who is a photographer and writer, asked if I wanted to meet on occasion to discuss shorter works of prose. The last time I was in a reading group was in 2015, so I jumped at the chance to discover some new writing that I might not normally come across.

This past week, among other things, we read an essay by Virginia Woolf on character called Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown. Though the text is dated, one line did spark a rather wide-ranging debate between us. In discussing famous novels like War and Peace, Pride and Prejudice, and Tristan Shandy, Woolf states:

… if you think of these books, you do at once think of some character who has seemed to you so real (I do not mean by that lifelike) that it has the power to make you think not merely of it itself, but of all sorts of things through its eyes …

Woolf doesn’t go into further detail about how she differentiates between real and lifelike, but my friend stepped in, likening this difference to how the subject of a painting might be portrayed by different artists—photo-realistically by one, or in impressionistic jabs by another.

The quote also piqued my curiosity beyond visual representations. I couldn’t help but wonder how Woolf might view today’s auto-fiction. What does character mean for the writer working in this space?

While fiction writers of certain periods certainly focused on mundane activities, auto-fiction tends to put an emphasis on these things. While hard, big F fiction novelists might focus only on activities that are pertinent to the story, the auto-fictionist might revel in mundane detail. There have been plenty of examples, in recent years, of writers working in auto-fictional spaces who, sometimes to the chagrin of readers, lean on the mundane. Ben Lerner does this, with his joint rolling and shitting. Rachel Cusk too, with her long monologues. But it’s probably Karl Ove Knausgard who dives the deepest—and at times, perhaps to boring affect.

Characters who are real, I guess, are those that are only exposed on the page in impressionist relief. Those that are lifelike? They require six volumes.

So how does the auto fictional writer then toe the line between real and lifelike, something which I believe is necessary, and keep things interesting? The secret might lie in how real the real is, and how lifelike the lifelike might be. Representation matters here—not only how the character is represented, but also, the things around the character. It is in the symbolization of the lifelike, and what this symbolization represents for the character, that makes mundane details interesting. The mundane shouldn’t be represented simply as a laundry list (unless that’s the point, and that point should be brief); instead, these symbols should only act as a representation, in that moment, of the characters wants and desires.

Or, we should think of the mundane as a kind of purgatory, as a border between where the character sits in time and space, and the unrealized Real they want to obtain (which is very likely where the conflict will arise). In this imagining of the mundane as narrative device, a character wants something, which is symbolized by the mundane, because they believe it will fulfill them. They strive to get this want, which again is momentarily represented by the mundane, and the conflict arises from whether they obtain it or not, depending on the arc of the story.

In The Sublime Object of Ideology by Slavoj Žižek, the philosopher explicates Lacan’s motto of ne pas céder Sur son désir (to not give away one’s desire) by suggesting that:

… we must not obliterate the distance separating the Real from its symbolization: it is this surplus of the Real over every symbolization that functions as the object-cause of desire.

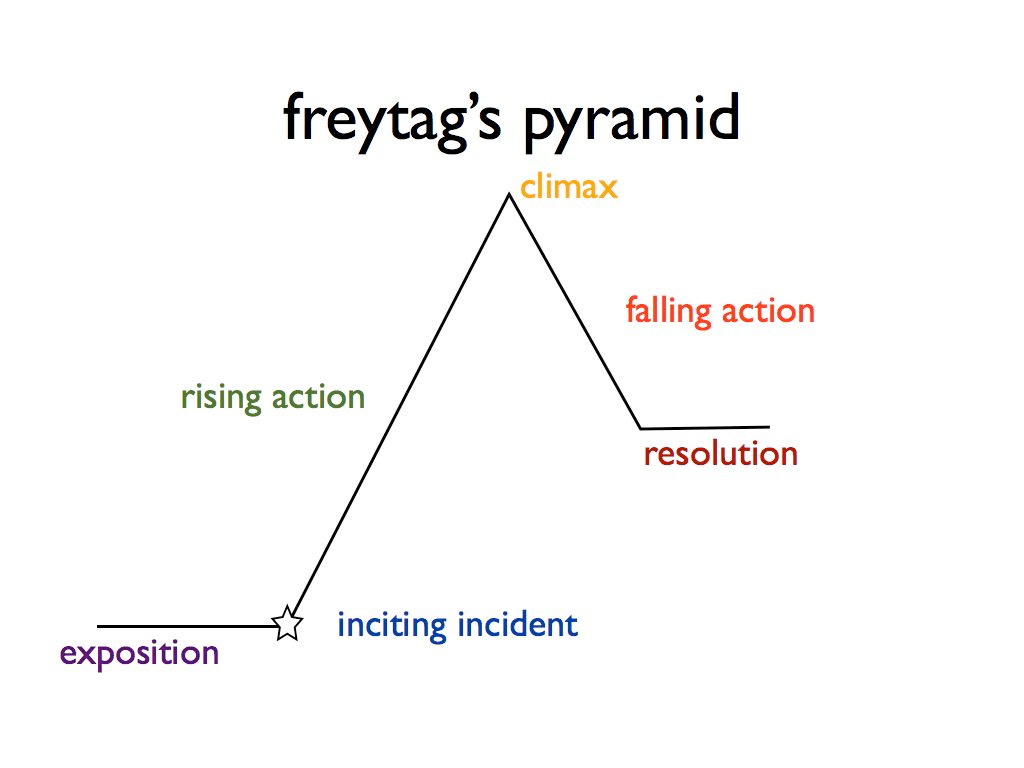

Meaning, in the case of using the mundane in fiction, that the conflict arises in the concept that there is, and always will be, something more. And perhaps this is a key way of thinking about character in the auto-fictional space, where so often nothing happens—pursuit of desire will always fail, even when the desire is obtained, because to obtain a desire always complicates. The Real (capital R) is sublime and can never be reached, because the real (lowercase r) we see is a fantasy we conjure. This failure to satisfy desire is as lifelike as anything else I can think of, and perhaps one way to resolve the trap auto-fictionists often find themselves in when trying to free themselves of the tyranny of Freytag’s Pyramid.

In the same way that Woolf backtracks in her essay, I’m going to posit that I’m grossly oversimplifying this argument. But, while laying under my blanket, recuperating with green tea and salty pretzels, I’m reaching for a desire to make myself understood—which is, perhaps beyond the abilities of someone running to the toilet every ten minutes—and built into that is naturally some small measure of failure.

But regardless of whether this thinking is sound, I can say, tentatively, that perhaps the best we can do, as writers, is to explore that mundane dissonance between reality and what is symbolized, and to find and dissect the desires we find there. It might be that in this region we discover the complexities that unfold in the hungry spiritual world where appetite is, unfortunately, never satiated.